Blog

Frankenstein: the genuine analyses that propelled the imaginary science

On January 17 1803, a young fellow named George Forster was hanged for homicide at Newgate jail in London. After his execution, as frequently occurred, his body was conveyed ceremoniously across the city to the Imperial School of Specialists, where it would be openly analyzed. However, what really happened was preferably seriously surprising over basic analyzation. Forster would have been zapped.

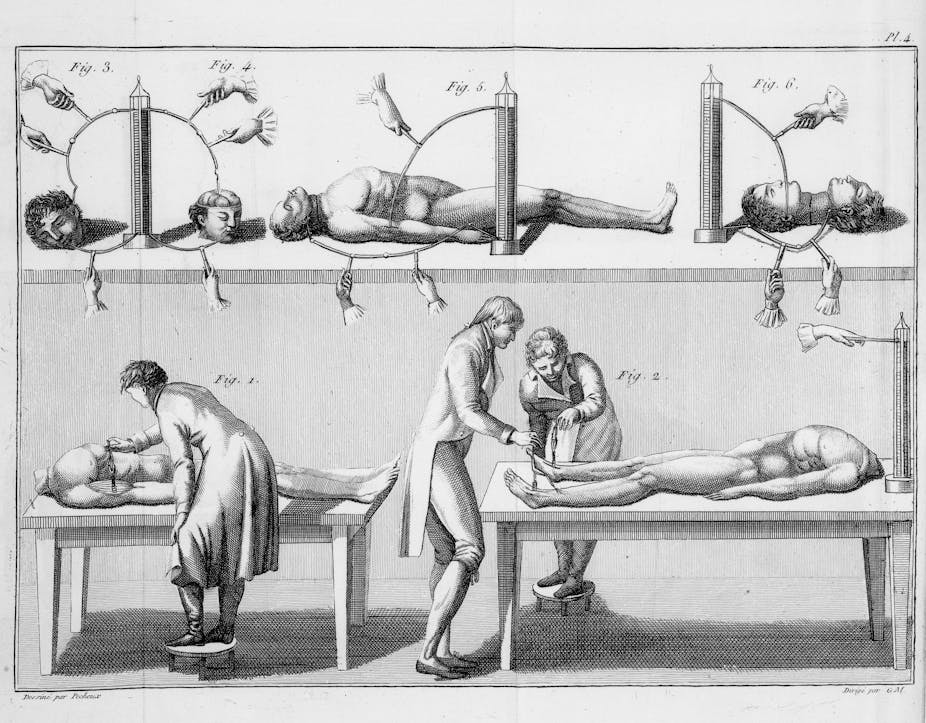

The analyses were to be done by the Italian regular savant Giovanni Aldini, the nephew of Luigi Galvani, who found “creature power” in 1780, and for whom the field of galvanism is named. With Forster on the chunk before him, Aldini and his colleagues began to explore. The Times paper detailed:

On the principal use of the cycle to the face, the jaw of the departed lawbreaker started to tremble, the abutting muscles were terribly twisted, and one eye was really opened. In the ensuing piece of the cycle, the right hand was raised and grasped, and the legs and thighs were gotten rolling.

It focused on certain observers “as though the pitiable man was just before being reestablished to life.”

When Aldini was probing Forster that there was some particularly close connection among power and the cycles of life was basically extremely old. Isaac Newton conjectured along such lines in the mid 1700s. In 1730, the English cosmologist and dyer Stephen Dim exhibited the rule of electrical conductivity. Dim suspended a vagrant kid on silk strings in mid air, and set an emphatically charged tube close to the kid’s feet, making a negative charge in them. Because of his electrical confinement, this made a positive charge in the youngster’s different limits, making a close by dish of gold leaf be drawn to his fingers.

In France in 1746 Jean Antoine Nollet engaged the court at Versailles by making an organization of 180 illustrious watchmen bounce all the while when the charge from a Leyden container (an electrical stockpiling gadget) went through their bodies.

It was to shield his uncle’s speculations against the assaults of adversaries, for example, Alessandro Volta that Aldini did his trials on Forster. That’s what volta guaranteed “creature” power was delivered by the contact of metals instead of being a property of living tissue, yet there were a few other normal logicians who took up Galvani’s thoughts with energy. Alexander von Humboldt tried different things with batteries made totally from creature tissue. Johannes Ritter even completed electrical examinations on himself to investigate what power meant for the sensations.

The possibility that power truly was the stuff of life and that it very well may be accustomed to bring back the dead was unquestionably a natural one in the sorts of circles in which the youthful Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley – the creator of Frankenstein – moved. The English writer, and family companion, Samuel Taylor Coleridge was intrigued by the associations among power and life. Keeping in touch with his companion the scientific expert Humphry Davy in the wake of hearing that he was giving talks at the Regal Foundation in London, he let him know how his “rationale muscles shivered and contracted at the news, as though you had exposed them and were zincifying the life-deriding strands”. Percy Bysshe Shelley himself – who might turn into Wollstonecraft’s significant other in 1816 – was one more lover for galvanic trial and error.

In 1814 the English specialist John Abernethy made a lot of a similar kind of guarantee in the yearly Hunterian address at the Illustrious School of Specialists. His talk ignited a vicious discussion with individual specialist William Lawrence. Abernethy guaranteed that power was (or alternately was like) the imperative power while Lawrence rejected that there was any need to summon an essential power by any means to make sense of the cycles of life. Both Mary and Percy Shelley surely had some awareness of this discussion – Lawrence was their PCP.

When Frankenstein was distributed in 1818, its perusers would have known all about the idea that life could be made or reestablished with power. Only a couple of months after the book showed up, the Scottish physicist Andrew Ure did his own electrical tests on the group of Matthew Clydesdale, who had been executed for homicide. At the point when the dead man was jolted, Ure stated, “each muscle in his face was all the while tossed into unfortunate activity; rage, ghastliness, hopelessness, pain, and loathsome grins, joined their revolting appearance in the killer’s face”.

Ure announced that the examinations were frightful to such an extent that “few of the onlookers had to leave the loft, and one man of honor swooned”. It is enticing to conjecture about how much Ure had Mary Shelley’s new clever as a primary concern as he did his tests. His own record of them was absolutely purposely written to feature their more shocking components.

Frankenstein could seem to be dream to present day eyes, yet to its writer and unique perusers there was nothing incredible about it. Similarly as everybody is familiar with man-made consciousness currently, so Shelley’s perusers had some awareness of the potential outcomes of electrical life. Furthermore, similarly as man-made reasoning (simulated intelligence) summons a scope of reactions and contentions currently, so did the possibility of electrical life – and Shelley’s novel – then.

The science behind Frankenstein advises us that ongoing discussions have a long history – and that in numerous ways the details of our discussions not set in stone by it. It was during the nineteenth century that individuals began pondering the future as an alternate nation, made from science and innovation. Books, for example, Frankenstein, in which writers made their future out of the elements of their present, were a significant component in that better approach for contemplating tomorrow.

Contemplating the science that caused Frankenstein to appear to be so genuinely in 1818 could assist us with considering all the more cautiously the manners in which we ponder the potential outcomes – and the risks – of our current fates.

If you are interested in Frankenstein-Inspired designer products, please see more at Frankenstein Collection here!